![]()

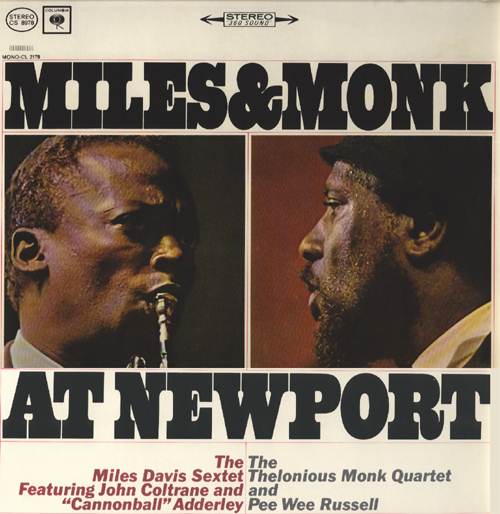

"Miles and Monk at Newport" |

![]()

|

Personnel: Miles Davis (tr), John Coltrane (ts), Julian "Cannonball" Adderley (as), Bill Evans (p), Paul Chambers (b), Jimmy Cobb (d). Adderley sits out on "Bye Bye Blackbird"

Songs:

1. Introduction by Willis Conover

2. Ah-Leu-Cha

3. Straight, No Chaser

4. Fran-Dance (aka Put Your Little Foot Right Out)

5. Two Bass Hit

6. Bye Bye Blackbird

7. The Theme

It was a night dedicated to Duke Ellington. That is, the 1958 Newport version of this two CD package of combo jazz given the misleading title of Miles And Monk At Newport. It was a memorable night for a variety of reasons, perhaps tops among them being the night's general disorganization, with starting times for musicians thrown off combined with an excessive gaggle of press. In fact, most critics considered this opening night of July 3 to be comprised of lackluster performances. This lost point is hard to believe when you consider the lineup: the Ellington band (featuring the Ellington Alumni all-stars, Gerry Mulligan, and Mahalia Jackson), the Dave Brubeck Quartet, Marian McPartland Trio, and the Miles Davis Sextet featuring John Coltrane.

The other half of the Newport program here jumps to 1963 with the Thelonious Monk Quartet featuring clarinetist Pee Wee Russell. Celebrating its 10th anniversary, the Newport (Rhode Island) Jazz Festival was recovering nicely from its now-infamous 1960 riot, when a reported 12,000 drunken adolescents stirred things up surrounding Freebody Park, apparently giving jazz a bad name and festgoers and doers fears of no more Newports. Ironically, 1963 saw the biggest jump in attendance since that dark year, reaching an overall high of 36,000. In addition to the "meeting" of Monk with the veteran Russell, there was trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie playing with vibraharpist Milt Jackson, Sonny Stitt joining forces with Maynard Ferguson's band, the Gerry Mulligan Quartet with Art Farmer and Jim Hall, and Sonny Rollins teaming up with Coleman Hawkins.

The strangest pairing easily had to be the inimitable, 57-year-old Russell blowing with the Monk quartet. The sight of these two eccentrics together on the same stage no doubt was amplified by the relatively straight visage of Monk's regular sidemen--tenor saxophonist Charlie Rouse, bassist Butch Warren (substituting for John Ore), and drummer Frankie Dunlop, all men (especially the rhythm team) known for their steady, consistent supporting roles. The idiosyncracies were to be left mainly with the featured stars. Monk's earthy-yet-transcendent style--capable of pulling in elements of stride and even early jazz--at times surrounded the older Russell even as Russell's distinctive stick wound its way around and through Monk's offcenter and boppish "Blue Monk" and "Nutty." The effect was one of an attempted generation bridging if not actual communion.

As for their program, there were no real surprises. (An aside: You'll notice self-important emcee Willis Conover introduces the Monk set by announcing that Monk's set ends with "Played Twice' and "Bright Mississippi.") The circumstances for the meeting, however, were a tad unusual. Actually, the first cause for Monk and Russell coming together was a quite mundane one: namely, that both were new Columbia recording artists, Russell having just recorded his New Groove with valve trombonist Marshall Brown (more on Monk's new music below). So, it was a kind of label/business thing on the one hand. On the other, and more interestingly, it appears that Russell--well known for his work with trombonist Jack Teagarden and trumpet legend Bix Beiderbecke and usually heard in Dixieland settings with trad revivalists like guitarist Eddie Condon--had done a little homework ahead of time, catching the Monk group at New York's Five Spot. From there, he learned more about Monk's live repertoire, which included the usual combination of originals with the occasional standard. Russell also learned firsthand how the bond operated on stage, the schematic of solos, tempos, arrangements, etc. From here, and what may have helped him to rest easier in front of a big crowd like the one at Newport, Russell picked the songs he wanted to play with the band (just two). Perhaps this unusual request was granted because the group wasn't able to rehearse with Pee Wee ahead of time.

For Monk and his band, the music was more or less business as usual. This set caught his group striding between two new quartet albums-Monk's Dream (his debut for Columbia) and its follow-up, Criss-Cross--and a third, titled Big Band And Quartet in Concert. Fresh from Riverside Records, Monk's Dream got his name out to the wider record-buying public, thanks to Columbia's greater market reach. Dishing up more of the same solid-yet-slightly-surreal mix of Monk plus standards, both quartet studio albums, incidentally, were produced by Teo Macero, Miles' and now Monk's regular producer (and this two-CD set's producer). As for the music on Miles And Monk At Newport, it varies only in its addition of Russell and the substitution of Warren for Ore on bass; otherwise, what we get is a live version of Monk's regular plate, including his newly recorded "Criss-Cross," but oddly foregoing any standards.

In retrospect, an opportunity was missed when Monk and Russell, for whatever reason, chose not to duet. Certainly, there was a great deal of material they cherished in common. If nothing else, a duet or two might have drawn out their distinct musical vocabularies, giving us a more complete picture as to why these two jazz greats ended up on the some stage. (if nothing else, what would Russell have done with "Epistrophy," "Light Blue," and "Criss-Cross" had he played on them?) Oh well, the history of music is filled with such near-misses.

As stated above, the music was more a blowing session than anything else (e.g., notice the times on "Nutty' and "Blue Monk"). A propulsive version of "Criss-Cross" is followed by a relatively delicate "Light Blue,' the interplay between soloists Monk and Rouse an enjoyable study in contrast (if not too dissimilar from their studio work). By and large, Rouse's playing tends toward the robust and energetic; in other words, typical Rouse. Not that he avoided the lyrical side to his playing. Hardly, his playing on "Light Blue' is sweet. Next to Russell and Monk, however, his tenor casts the fullest shadow over proceedings that, by and large, sound playful if not a little... nutty. Speaking of which, the middle portion of the set brings on Pee Wee, with his typically pointy, wayward phrasings for "Nutty" and "Blue Monk." When Monk lays out port-way through both tunes, Russell takes the music to a decidedly different place, bringing Warren and Dunlop with him. It's as if he recasts Monk's alternating dark colors and playful melodies by simply upending them, the sound of his thin clarinet voice literally a reed in the wind. For this listener, Russell's pipe is the most unusual sound Monk ever dragged in.

Listening to Thelonious, some might say his comping behind Rouse and especially Russell is heavy-handed. Who knows? Playing outdoors on a stage like Newport's might've been a challenge for anyone to be heard. No matter, to these ears, Monk's secondary comp lines on medium-gaiters "Nutty" and "Blue Monk" literally complement--rather than compete--with the soloist, prodding Rouse and Russell along without stealing the show. By this time, in 1963, Monk's solo style had been so established that his "unswinging" swing, full of rhythmic displacements and simple phrases, works wonderfully even if he sounds like he's devoid of ideas (listen to the end of his solo on "Blue Monk").

Initial buyers of Miles And Monk At Newport might've figured the two jazz greats performed at the some actual festival, if not together on the same stage. Certainly, they had played together in the post, but not on this record, as Conover's original liner notes made clear. (Unfortunately for Bill Evans and fans alike, Conover, who was there, incorrectly listed Wynton Kelly as Davis' pianist when, in fact, Evans performed with the hand that day in 1958!) The Davis material here, perhaps more than any other, has been sliced and diced into a variety of album packages. Now, with this release, we have the whole concert together on one disc for the first time. (For the original release of Miles And Monk At Newport, "Bye Bye Blackbird" and "The Theme" were left off.)

Some background: The year 1958 was a busy one for Miles the recording artist. Having played the sideman role for fellow horn player Julian "Cannonball" Adderley on his Somethin' Else in March, Davis went on to record the very well received Milestones with his sextet--including Adderley as well as Coltrane in the front line the following month. This album featured parting members Red Garland on piano and drummer Philly Joe Jones, along with bassist Paul Chambers. (Milestones was also Davis' last mono recording of note.) In May, Bill Evans and Jimmy Cobb joined the band, and they all went into the studio to record a series of tunes that eventually found their way onto various Davis albums. And right before the Newport set, Davis, along with a number of other jazz vets, recorded a variety of jazz standards for French composer/arranger Michel Legrand under the unlikely title Legrand Jazz.

Which brings us to Duke Ellington Night and Newport July 3, 1958. For many critics, the music was okay of best. In Down Beats festival review, Don Gold heard a "...group [that] did not perform effectively. Although Miles continues to play with delicacy and infinite grace, his group's solidarity is hampered by the angry young tenor of Coltrane. Backing himself into rhythmic corners on flurries of notes," Gold noted, "Coltrane sounded like the personification of motion-without-progress in jazz. What is equally important, Coltrane's playing apparently has influenced Adderley. The latter's playing indicated less concern for melodic structure than he has illustrated in the past."

Depending on your views of what jazz is about, whether someone is "angry" or not may seem irrelevant. Besides, it's always a somewhat dubious enterprise to guess someone's emotional state when playing. More to the point, the sound level of one's playing is significant. In this case, Coltrane was all over the place in a fascinating, if trying, display of virtuosity. More trying, however, was the nearly suffocating Jimmy Cobb, recorded as he was heard that night. Again, Gold weighs in, this time more on the mark: "Although Chambers continues to be one of jazz's most agile bassists, he was drowned often by Cobb's oppressive support!" He goes on to mention Bill Evans being a victim as well. In fact, the whole band suffers on all tunes with the notable exception of "Fran Dance" and, to some extent, "Bye Bye Blackbird," numbers that required Cobb to lighten up a bit.

Every tune here had been previously recorded by a Davis group of one kind or another, the most recent addition being his "Fran Dance," recorded during that May '58 session referred to above. All in all, the feel of these performances, from the audible foot-stomping by Miles to the generally up-tempos, suggests a hard-bop attitude, Charlie Parker's "Ah-Leu-Cha" and John Lewis' "Two Bass Hit" leading the charge. Evans, the romantic expressionist, fairs least well in this setting, while Coltrane is obviously given room to explore and experiment. His solo on "Bye Bye Blackbird," for example, sounds unfinished. Adderley is used more as a foil, it seems (he lays out on "Blackbird' altogether).

Granted, the sound of Coltrane's tenor might’ve sounded angry to some; especially next to Adderley's relatively smooth, boppish alto and Miles' haunting, brooding mute and more tempered, lyrical open horn. But what's wrong with being angry? It's open to question the musical effect Coltrane had on his bandmates. Besides, and apart from the presence of Jimmy Cobb, this set documents a kind of work-in-progress of one of the most significant musical groups ever assembled. Later this some month, Davis went on to record the legendary Porgy And Bess with Gil Evans; while this group, with Wynton Kelly on one tune, would go on to record one of the greatest jazz albums of all time the following year, Kind Of Blue.

It's significant that Miles & Co. were true to form at Newport 1958. As Don Gold also mentioned in his review: "On an Ellington night, the Davis group's repertoire included six tunes, none associated with Duke... Asked backstage why his group did not perform Ellington tunes, Miles logically declared that performing familiar material effectively would be the best sort of tribute."

Here, here. I'm reminded of the Miles album Get Up With It, from 1974, the year Ellington died. Inside the two-record set is a left-hand image of Miles sitting on a stool with hands in pockets, looking reflective into the fold of the cover. The right-hand side of the jacket includes a simple, modestly sized "FOR DUKE" written dead-center. The image of Miles is positioned as if he were looking of that phrase. More significant is the "tribute" number, "He Loved Him Madly" (from "We love you madly," a phrase Ellington used repeatedly over the course of his career when speaking to his audiences). Taking up all of side 4, to most ears, the music of "He Loved Him Madly" was, and is, an incredibly uncharacteristic tribute to Ellington, what with its almost-ambient, subdued, dirge-like cadences, its use of flute (!) and electric guitar, and lack of typical song form, not to mention length.

By contrast, it's easier to see how a set like this one from Newport--sounding closer to the source of jazz (and Ellington) and one most fans could identify with--could be a personal statement from Miles to Duke. Over the course of his career, Davis never recorded any Ellington songs. Consequently, whatever musical links existed between the two (at least from Davis to Duke) had to run very deep, beyond casual recognition. Thus, to hear the connection between Miles and Duke, the listener needed, and needs, to really listen. Maybe this live set gives us only a cursory tribute to Duke, and Miles was just bluffing. Then again, who knows?

John Ephland Down Beat May 1994